A recent headline reminded us that we were in a raging bull run.

It does have a nice feel to it. But this article is not about to debate whether we are experiencing the mother of all bull markets or are in the midst of a rapidly aging one where the day of reckoning is due. Such market prognostications are perilous at best. The point to be made is that no matter what the state of the market, adhering to an astute investing strategy is always wise.

In his book The Intelligent Investor, Benjamin Graham (the father of value investing) makes a bold statement: Confronted with a challenge to distill the secret of sound investment into three words, we venture the following motto, MARGIN OF SAFETY.

All the legends of value investing will nod their heads in approval as it is central to their concept of investing. And will probably stay that way as long as humans are unable to accurately predict the future. Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger, Seth Klarman, Joel Greenblatt and numerous others consider this principle to be the cornerstone of investment success.

So what does that mean?

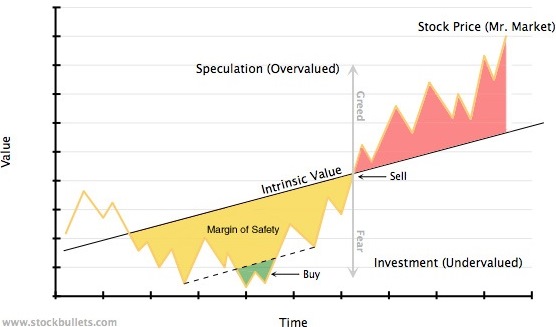

To break it down to its simplistic best, it means figuring out what a stock is fundamentally worth and paying a lot less for it.

First, you value the stock – you set an estimated intrinsic value. And then you wait for the price to fall significantly below this intrinsic value. When it does, you buy. This is call the margin of safety.

So instead of buying a stock just because a furious bull run is on and prices of stocks are rising daily, hold on. Exercise patience and buy the stock only when it's selling at a decent margin of safety to your estimate of its intrinsic value. Don't even think about the overall direction of the stock market, because that's impossible to predict with any consistency.

Still lost?

Buffett explains it with a brilliant analogy. Just think, if you were asked to build a bridge over which 10,000-pound trucks were to pass. Would you build it to hold exactly 10,000 pounds? Of course not--you'd build the bridge to hold 15,000 or 20,000 pounds. That is your margin of safety.

Now apply that to stock investing.

Let’s say you estimate the intrinsic value of a stock at Rs 100. You believe that is what the stock is really worth. But you don’t buy it. And it would be foolish to buy it at Rs 98 too. There’s no room for error. But if you buy it at Rs 70, then you have a 30% margin of safety. The Rs 30 difference between estimated intrinsic value and purchase price is the margin of safety. This is the buffer in case unforeseeable events alter the business landscape. Or, if you are wrong on your intrinsic value calculation by placing it too high, you still have a strong chance of making money. By purchasing the stock at Rs 70, it allows you to be wrong by 30%. Since there are no guarantees in stock market investing, this will not guarantee that you won’t make a loss but it does vastly reduce the likelihood of your doing so.

The below visual from Old School Value should give you a graphical understanding.

- As Charlie Munger says, no company, however wonderful, is worth an infinite price. You must fundamentally work out its worth and then apply a margin of safety to make money.

- Finding an investment opportunity with a substantial margin of safety is not that common. So be patient.

- Even strong bull markets have periodic slumps or corrections. Those phases may throw up some buying opportunities.

- There is no fixed margin of safety. According to Warren Buffett if you understand a business and if you can see its future perfectly, then you obviously need very little in the way of margin of safety. Conversely, the more vulnerable the business, the larger the margin of safety you require. A start-up would require a larger margin of safety than a blue chip. A dividend paying company known for its future secure cash flows will required a lower margin of safety.

- The larger your margin of safety, the better. But it all depends on the business in question. If the firm is not very risky, you could be content with a 15-20% discount to its intrinsic value. If the firm is riskier than average, you may demand a 30-40% discount.

For example, infotech stocks are currently quoting below their intrinsic value. Morningstar’s equity analyst Andrew Lange has put the FVE of Infosys at Rs 1,177, with a consider buy at Rs 706 and consider sell at Rs 1,824. For Wipro the FVE is Rs 650, with a consider buy at Rs 390 and consider sell at Rs 1,007. For TCS, the FVE is Rs 2,725, with a consider buy at Rs 1,635 and a consider sell at Rs 4,223.75.#

(# FVE – Fair Value Estimate. At Morningstar the FVE is the intrinsic value because we use the Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) model to derive our fair value. So we look at the long term value potential as well and not just the current market value. Valuing a company based solely on the current PER would not be equivalent to its intrinsic value.)