While there are various investing principles that form the bedrock of any strategy, grasping the nuances is what separates the men from the boys.

Author and investor Vitaliy Katsenelson, is the CEO at IMA. Here he explains how nuances matter in stock analysis, and illuminates the reader by using Softbank as an example.

It seems that Softbank stock has been hated and misunderstood every day we’ve owned it – until recently, when Eric Savitz at Barron’s wrote a front-page story that made many points that I’ve made over the years – Softbank is a deeply misunderstood 50 cent dollar run by an ingenious CEO.

We first bought Softbank in 2015. At the time the market was focusing on Sprint’s then “imminent” demise. Our argument was that Softbank stock was incredibly undervalued, with or without Sprint. Even if Sprint went bankrupt, it would reduce Softbank’s value per share by only about $5, from $45 to $40. The stock was in the mid-20s then (the stock split 2 for 1 since).

The market was missing a very important point: Since Softbank owned over 80% of Sprint, it had to consolidate Sprint’s debt on its balance sheet, which overstated Softbank’s true indebtedness by more than $40 billion. Sprint was an independent legal entity, and thus Sprint’s debt was non-recourse to Softbank. I cannot tell you how many articles I read at the time that focused on Sprint’s problems and Softbank’s indebtedness and failed to see this important nuance. Neither traditional nor social media are good with nuances.

Masayoshi Son, Softbank’s founder, made Sprint his highest priority. He self-appointed himself “Sprint’s Chief Network Officer” and worked for one year to turn Sprint around. Sprint’s business stabilized. And now it seems that the Sprint–T-Mobile merger has been approved, Softbank will become a minority shareholder of the combined entity, and Sprint’s debt will “magically” migrate from Softbank’s balance sheet to that of the new entity. This has zero economic impact on Softbank but will make its balance sheet appear less indebted.

We did not require a sharp pencil to make this investment; we just needed a crayon. We knew it was worth a lot more. It owned a third of Alibaba, which is dominating Chinese e-commerce and still growing 30% per year; Softbank KK, the third largest, and very profitable, telecommunications company in Japan; Yahoo Japan, which was publicly listed; and Sprint, which was worth between something and zero. It had a plethora of assets that we could not value, but every time they got sold Softbank recognized astronomical returns and billions of dollars of profit.

If you added it all up, we were basically buying $1 for 50 cents, and most importantly, we were getting Masayoshi Son for free. He built Softbank out of nothing into one of the largest companies in Japan. His involvement in Softbank is incredibly important, because he owns 20% of the company and had an incentive to grow this metaphorical $1 we were buying for 50 cents into $1.50 and then to $2. And that is exactly what has happened, four years later. Though the stock price has almost doubled since, as Eric Savitz writes,

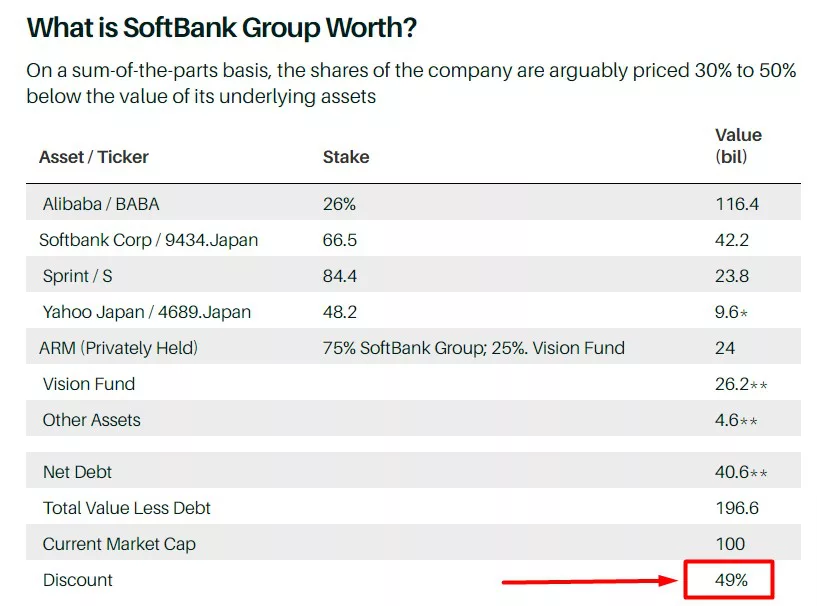

“The stock is cheap. Crazy cheap. On a sum-of-the-parts basis, its shares are arguably priced 30% to 50% below the value of their underlying assets.”

Savitz includes a table in the column that shows that sum-of-parts analysis of Softbank, by which he concludes that if you add up Softbank’s assets, it is still a 50-cent dollar. Our research brings us to a similar conclusion.

Though the media will continue to focus on the questionable ethics of the its CEO, WeWork is a multi-billion-dollar pimple; and just like Sprint a few years ago, it will reduce what Softbank is worth by a few dollars if it goes bankrupt during the next recession; but ultimately it is irrelevant to Softbank’s success as an investment.

And then there is the Softbank private investment vehicle, the Vision Fund, which it uses to invest in emerging technology companies. Actually, after Masayoshi Son spent $100 billion on it, he created a second, even larger, $108 billion Vision Fund, whose investors include Microsoft, Apple, the Saudi wealth fund (not necessarily a positive), and others.

Am I concerned that Son is spending money at a $100 billion a year clip? He has said that despite the speed at which it spent money, the Vision Fund looked at thousands of companies and invested in 70, only 3%. Also, I remind myself that while Softbank is a large position in our portfolios, for Son it is his life’s work and represents basically all of his net worth. And the best part, again, is that the stock is so cheap; and if the first fund goes to zero, Son’s reputation will be tarnished and the billions Softbank put into the fund will we wiped out, but our Softbank investment will still work out.

Softbank is contributing $38 billion to the second fund – a large sum of money even for Softbank. Though Softbank’s large discount to fair value could afford seeing the first fund do poorly, we won’t have that luxury if both funds collapse. But this is a bit of a premature discussion considering that the first fund has made a lot of money so far and the second one is still being formed.

We’ll be looking very carefully to see where Softbank gets this money and how the deal is structured. I suspect that Softbank will be selling its stake in T-Mobile– Sprint once the deal is done. Son has mentioned in the past that companies in this portfolio that have matured will be the source of capital that will flow into the ones that have growth ahead of them. This is one of the reasons why Softbank took Japan Telecom public.

Also, and this is a very important nuance that is often missed – Son structures deals with an asymmetry: heads he wins, tails he doesn’t lose much. Here is an example. A bit more than a decade ago Softbank made a huge bet on Vodafone KK, which at the time was the worst-run telecom in Japan. It was a very gutsy move – Vodafone KK was a very large bet for then-small Softbank. But Son structured the deal in such a way that even if the investment didn’t work out, the loss to Softbank, though unpleasant, would be manageable. One the other hand, if the turnaround succeeded – which, thanks to Son, it did – it would be a terrific investment.

This nuance was lost in the media then, which liked to refer to him as the Japanese cowboy, and it is lost today when people write about the Vision Fund.

Here is what Son said in February about the “debt” structure of the Vision Fund.

”[W]e have another characteristic of this Vision Fund, which is that in ordinary cases of those private equities or venture investments, we only invest in equity to get the commitments of the capital. So the capital consists only in equity, but in our case, we put it into two parts. One is the fixed distribution, which is 7%, is scheduled for the preferred equity. And one other is the normal equity. So in terms of stocks, it’s equivalent to preferred stock and common stock. Preferred equity is not borrowing. When fund fails, we are still not obliged to pay back. So again, it’s equivalent to preferred stock. We are not [in]debted. But if performance of the fund doubles and triples, the part of preferred equity is 7% fixed distribution. So the performance stays the same in terms of distribution, 7%, even though the investment doubles or triples.”

This little nuance that “debt” in the fund is actually preferred shares and thus secured only by the fund’s assets, and has no recourse to Softbank, is usually lost in most “binary” (good or bad) articles. But these little nuances matter, and without seeing them it is very difficult to be a good investor.