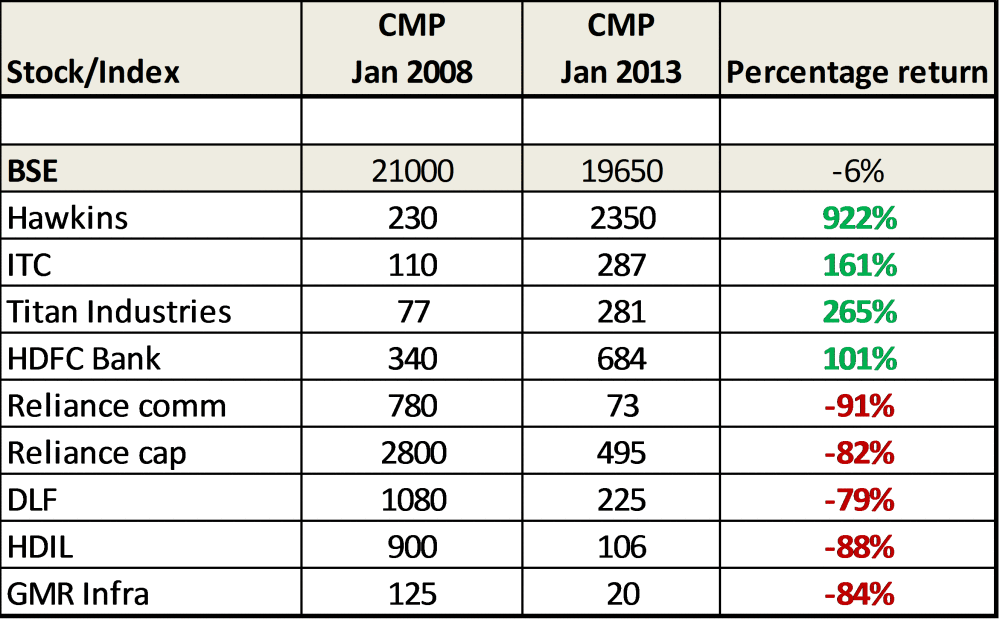

A few years ago, Gautam Baid came across an image that demonstrated how some stocks beat the Sensex hands down. (No, we are not getting into an active versus passive discussion.)

The article on IndianWallStreet Blog explained how Rs 20 lakh invested in stocks such as Hawkins, ITC, Titan, and HDFC Bank would have grown to almost Rs 1 crore in that 5-year period.

The same amount invested in Reliance Communications, Reliance Capital, DLF, HDIL and GMR Infrastructure would have shrunk to Rs 3 lakh over that time. That is some serious erosion of wealth.

The Sensex, on the other hand, would have returned -6%.

The writing on the wall was clear.

Good businesses create enormous wealth over long holding periods across market cycles. If one has the discipline to hold on during turbulent times and stay the course.

Gruesome businesses eventually destroy wealth, even if they experienced bouts of enviable popularity. That is because liquidity and sentiment drive the market index in the short term, while individual company earnings drive stock prices in the long term.

In his book, The Joys of Compounding, Gautam Baid makes a reference to the above image when discussing wealth creators.

In Going beyond technicalities in investing, I had written about his investing style and why he liked the business of Hester Biosciences. In this space, I am reproducing a few basic pointers from the book. This is not an exhaustive list for equity investors, but certainly a helpful one.

- Intrinsic Value should be a range of value.

The best outcome than an investor can hope to achieve when it comes to appraising business values is to come up with a range of values and then wait for the market to offer a price that is significantly below the lower end of the range – this gives you both a margin of safety in the event of your analysis being wrong and high returns if you are right.

Benjamin Graham in Security Analysis discussed the concept of a range of value where he emphasized that the analysis of a stock is not to determine exactly what the intrinsic value is; an indefinite and approximate measure is sufficient.

From this we can infer that Graham never intended for intrinsic value to be thought of as a single point estimate of value. Rather, he thought of it more as a concept of value.

- All earnings are not created equal.

Capitalize each business differently; $10 of earnings from a capital-light business like Moody’s, with its low reinvestment requirements, is worth a lot more than the same earnings figure from a capital intensive business.

Look at each business’s earning power, along with future prospects of the business, to decide how much one is willing to pay to acquire that business’s future cash flows. Determining the present value of all the future cash flows of a business involves looking at various aspects of a business’s DNA, including its capital intensity, business model durability, balance sheet strength, profitability, competitive position, future growth prospects, and management bandwidth, among other factors – all weighted and compared to the current price.

Predictability of cash flows is a very important factor. Less predictable cash flows needs to be discounted at a higher rate.

- Value traps are abundant and all-pervasive.

Value traps are businesses which appear to be cheap but are very expensive in reality. This could happen for a variety of reasons:

- Cyclicality of earnings: A low P/E stock may look cheap because the business is enjoying cyclically peak earnings

- App risk: A taxi company may look cheap based on past earning power, which existed before Uber arrived

- Bad allocation by management: The market may be punishing a business by assigning a low multiple to its earnings because the managers keep burning cash in bad projects and there is no prospect of such misallocations being stopped

- Governance issues: A business run by a crook may appear very cheap relative to the large amount of cash reported on its books, until that cash is siphoned off.

Most of the time, switching from a high P/E stock to a low P/E one proves to be a mistake. In the stock market, prices usually move first, and the reported fundamentals follow. A plummeting stock price in a steady market often turns out to be a harbinger of deteriorating fundamentals. What appears cheap or relatively inexpensive can continue becoming cheaper if industry headwinds intensify.

- Don’t be biased against high P/E stocks.

Investors with a bias against high P/E stocks miss some of the greatest stock market winners of all time. This is because, over 10 years or more, a high P/E company that’s growing earnings per share at a much faster rate will eventually outperform a lower P/E company growing at a slower rate, even if there is some valuation derating in the interim period for the former. If it comes to a choice between a 15% grower at 15P/E and a 30% grower at 40P/E, one should always choose the latter, whenever longevity of growth is highly probable.

- Don’t conflate ROIIC with ROCE.

When I look at high ROIC businesses, what I am really looking for is return on incremental invested capital (ROIIC), or the return a business can generate on its incremental investments over time. Don’t confuse ROIIC with ROCE. It is ROIIC less cost of capital that drives value creation. This is because even though legacy moat businesses with established franchises and low/no growth opportunities may have high returns on invested capital, if you purchase their stock today and own it for 10 years it is unlikely that you will achieve exceptional returns, because their high ROIC reflects returns on prior invested capital rather than incremental invested capital. In other words, a 20% reported ROIC today is not worth as much to an investor if there are no more 20% ROIC opportunities available to reinvest the profits. Mature legacy moat businesses with good dividend yield may preserve one’s capital, but they are not great at compounding wealth.

Let’s say Company A and Company B, each have an ROIC of 20%, but Company A can invest twice as much as Company B at that 20% rate of return. Then Company A will create much more value over time for its owners than Company B. Same ROIC but one is clearly superior to the other because it can reinvest a higher portion of its earnings, and thus will create a lot more intrinsic value over time. The longer you own Company A, the wider the gap gets between the investment results of the two.

Concluding…

The above are just few scant guidelines.

Baid has always cautioned that one must never forget that rationality and temperament are far more critical than raw intellect in the investment arena.

Understand human nature and use it to your advantage, don’t fall prey to crowd psychology and cognitive biases.