Last year Britain’s fast-fashion Boohoo brand got embroiled in a labour supply chain scandal. A workers’ rights group brought to light the dire working conditions and alleged that factories supplying its clothing were putting workers at risk of COVID-19 with little to no social distancing or PPE, and some that tested positive were told to continue working.

This had a detrimental impact on the brand, and its share price. Amazon, ASOS, Next, and Zalando were some retailers that instantly dropped Boohoo's brands from their websites, as they waited for the company to conduct its investigation. The company launched an independent review of its supply chain and cut its relationship with two suppliers. It is now considering linking executive bonuses to specific ESG targets.

Many investors and asset managers view ESG as a vague, feel-good, nice-sounding goal. And are convinced that the froth surrounding ESG will eventually run its course. They are probably right about ESG being a feel-good and nice-sounding goal. They are definitely wrong in assuming that it stops there.

ESG is the bedrock of Sustainable and Responsible Investing (SRI) and stands on the three pillars of Environmental, Social and Governance.

ESG refers to corporate activities that would maintain or enhance the ability of the company to create value over the long-term. But at the heart of ESG investing is that companies are more likely to succeed and deliver strong risk-adjusted returns if they create value for ALL stakeholders – shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers and wider society including the environment. Hence, it includes mainstream financial metrics and non-financial aspects of a business (environment, human capital, social capital, innovation, leadership, and governance).

Adhering to the principles of ESG is what strengthens the resilience of companies. What is simply a label to many is now getting constructively rationalized and intensely scrutinized.

A critical attribute of ESG adherence is the ability to foster social change and force transparency and accountability.

Last month, Rio Tinto shareholders rebelled over the renumeration to former CEO Jean-Sébastien Jacques and other executives who quit last year.

Rio Tinto previously defended the pay packages, saying that the three executives "did not deliberately cause the events to happen." But investors approved the updated remuneration policy to allow for more leeway to claw back share awards and bonuses when its reputation or "social license to operate" has been adversely impacted.

Here is the background: The company received blistering public criticism for its environmental and human rights violations in Australia. One was related to an abandoned mine leaking waste and poisoning rivers on the island of Bougainville. The other was the destruction of the caves at Juukan Gorge, a 46,000-year-old sacred Aboriginal site. In a submission to Australian parliament, the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura people stated that the “Juukan Gorge disaster tells us that Rio Tinto’s operational mindset has been driven by compliance to minimum standards of the law and maximisation of profit”.

Following the public outcry, BHP Group halted plans to expand a mine in Western Australia despite obtaining approval. The mining giant decided to do have prior extensive consultation with Aboriginal groups; the Banjima people.

The above incidents are clear-cut examples of why governance matters, and how stakeholders are taking an active role in holding companies accountable.

Kristoffer Inton, director of equity research – basic materials, Morningstar, explains how ESG matters because it identifies potential risks that could affect a stock price.

Just like investors would want to know if a company could run into trouble from having too much debt, or selling products in a declining industry, it is important for investors to consider ESG risks that could hurt a stock. These risks may not currently affect a company but have meaningful potential to.

For instance, chemicals companies face risks from environmental damage that can ultimately cost billions of dollars to clean up, such as asbestos lawsuits that left many companies bankrupt.

Beverage companies must continually monitor their water use as they may have to pay higher costs or even stop producing beverages if they use too much water.

Any company whose employees are unionized is at risk that their employees will go on strike due to poor working conditions.

By identifying and assessing these risks, we can use ESG analysis to better understand company risks.

ESG analysis provides valuable insights about factors that can have a significant impact on the financial metrics of a company. These non-financial factors are applied as part of our analysis process to identify material risks and growth opportunities.

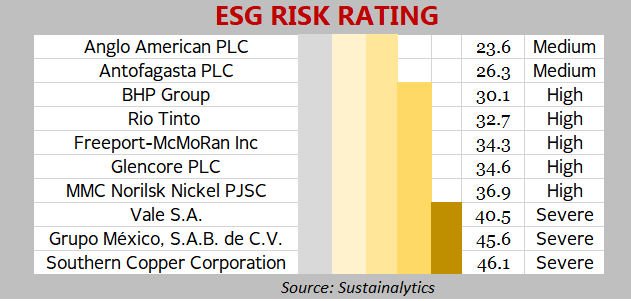

For instance, Sustainalytics, a leading independent global provider of ESG research and ratings, categorizes its company ratings across 5 risk levels:

- Negligible

- Low

- Medium

- High

- Severe

To stick with the above example, within its industry, Rio Tinto is categorised as High Risk with the top material ESG issues being Corporate Governance / Community Relations / Emissions, Effluents and Waste / Resource Use.