For thousands of years, people around the world have used fermented grains and fruits to make alcohol.

The earliest evidence that humans were brewing alcohol comes from residues in pottery jars found in northern China that date from 7,000 to 6,600 B.C. Between 3,000 to 2,000 B.C., Sumerians in Mesopotamia made beer. In ancient Egypt, bread and beer were staples in the daily diet. Ancient Greece was one of the earliest known centers of wine production; winemakers established vineyards as early as 2000 B.C. (source)

However, harmful use of alcohol has health and socioeconomic consequences. Production of alcohol also has environmental repercussions. As an investor, what is it that you must be aware of?

Here are some interesting perspectives from Morningstar's equity strategist for ESG, Kristoffer Inton.

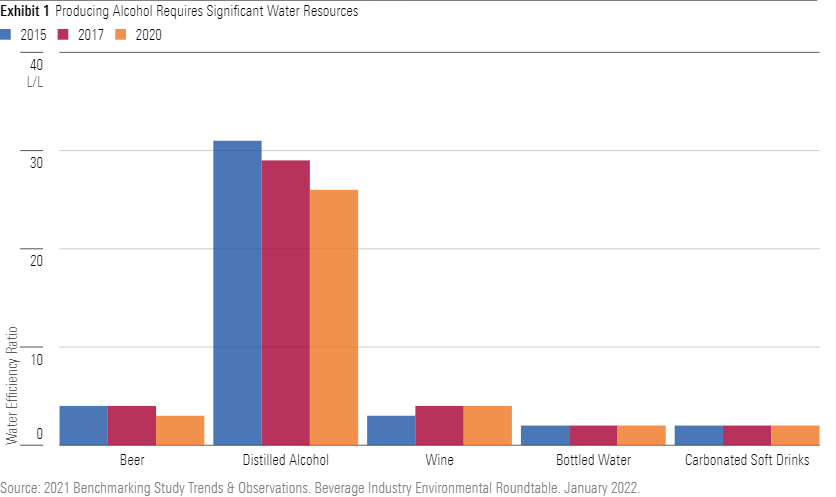

Based on assessments from Sustainalytics, the biggest environmental, social, or governance (ESG) risk for alcohol stems from water use. Indeed, beer contains roughly 95% water while liquors tend to contain roughly 40%-60% water.

But water isn’t just an ingredient. It’s critical to production, including cleaning, cooling, and packaging. And water is even more important given its direct impact on product quality and experience, as well as the growing of ingredients like barley, corn, and other crops.

Click on image to enlarge

Unfortunately, demand for water will likely exceed available supply, accelerating depletion of underground aquifers. Our analysis estimates unmet demand of 111 billion cubic meters for 2030. As more groundwater is needed, pumping from deeper levels will double water costs by 2030. And while the water cost to make a single bottle of beer would amount to roughly one tenth of a U.S. penny—a microscopic part of the retail price—water is still an important ESG issue for risks to a company’s reputation and other assets. In 2020, Constellation Brands abandoned a nearly complete brewery in Mexico after spending $900 million, over fears of worsening water shortages for local farmers.

These concerns are on the minds of many investors, including those that opt to not in invest in companies driving potential water shortages worldwide. But we think the risk is mitigatable.

First, both technology and process improvements can improve efficiency, lowering cost and opposition risk.

Second, we think economic moats, which describe how likely a company is to keep competitors at bay for an extended period, can help maintain margins. Moats in alcohol are largely due to cost advantage. While higher water costs would affect all equally, scale over fixed costs would still allow companies with moats to absorb increases better. Having a powerful brand could also help producers pass rising water costs on to customers

Of course, water issues aren’t the only rationale for some investors eschewing alcohol companies in their portfolio. Another important ESG risk to alcohol stems from health impacts. Indeed, mindful drinking, the increased popularity of abstinence, and health concerns have caused consumption to decline. We expect these trends to continue.

However, we think producers can also mitigate this social risk.

First, ongoing premiumization—that is, consumers willing to pay up for higher-quality beverages—can offset lost volumes with higher prices.

Second, investments in nonalcoholic beverages, such as energy drinks and kombucha, as well as no- or low-alcohol versions of beers, wine, and spirits, can match changing preferences while taking advantage of alcohol producers’ strong existing relationships with retailers and distributors.

There’s nothing wrong with exclusionary investing. This refers to excluding companies based on certain products/services, an industry, or certain corporate behaviors, like major controversies.

In addition to fossil fuels and weapons, sin stocks like alcohol and tobacco are common targets for values-based exclusionary investing, which simply means choosing not to own specific stocks or sectors because of your values.

But choosing to look away from an industry also means you might miss some great opportunities.

Also, while a focus on values might preclude owning these industries for many sustainable investors, the valuation effects from ESG risks are more nuanced. Simply avoiding investing in alcohol producers ignores offsetting factors that arguably contribute to a company’s sustainability.