Frontier markets are an often overlooked part of the emerging markets space, but offer exposure to the some of the most enduring themes driving growth across the world. But, as with any little-known investment area, myths abound about which countries are classed as frontiers, why, and whether they are worth investing in.

Myth 1: They are risky places I’ve never heard of

Unless you’ve just flown in from another galaxy, you’ll doubtless have heard of the countries which make up the MSCI Frontier Markets Index. It comprises 28 countries including Bahrain, Kuwait, Nigeria and Vietnam.

The term “Frontier” may sound a little scary but all it means is that these markets are not yet developed enough to be classed as emerging markets.

Despite that, many of them are driven by the same trends as countries such as China, Brazil and India. Populations are young and getting wealthier, meaning they have more disposable income to spend. That helps companies increase earnings and economies to grow.

Leigh Innes, portfolio specialist at T. Rowe Price likes Vietnam for this reason, where she rates Mobile World Group, which has a growing business in fresh food retail, and jewellery company PNJ. She adds: “A lot of these countries have had conflicts in the past but now have peace, improving politics and improving economies and that all attracts people into the country. You need to find good companies that can take advantage of that backdrop.”

Myth 2: They are all the same

Developed markets such as the U.K. and U.S. tend to be interlinked because of global trade and companies doing business internationally, and that means their economies often rise and fall in tandem. But many of the companies listed in frontier markets tend to be more domestically focused, which means what happens in other countries doesn’t really affect them.

That should mean performance of the index is less volatile generally, because a recession in one frontier market doesn’t have the same domino effect it might in the developed world. Emily Fletcher, co-manager of the BlackRock Frontiers Trust says: “What drives returns in Nigeria, for example, is largely independent from geopolitical events impacting Argentina, Pakistan or Saudi Arabia.”

Of course, it does leave them vulnerable to any shocks within their own borders. Sri Lanka, for example, has had a difficult period after a terrorist attack last year. Still, Fletcher is positive on a number of stocks there including Hatton National Bank and ice-cream maker Ceylon Cold Stores.

When countries continue to develop, they graduate to the emerging markets index, in the same way a growing company might move from a small-cap to mid-cap index.

This year Kuwait is set to move up to Emerging Markets status and many stocks in the country have been boosted by this.

Fletcher says market euphoria around such upgrades can often push share prices up to a point where valuations start to look expensive: “We are happy to take advantage of this strength, take profits and redeploy this money into other areas of the portfolio.”

Myth 3: Companies are poorly governed

Many investors might assume that the standard of governance in emerging or frontier markets will be poor compared to those in developed markets, but it is important not to make a blanket assumption.

Nigeria passed a code of corporate conduct last year, Innes points out, while Vietnam has made changes to limits on foreign ownership and most listed companies across these markets report quarterly and to global standards.

“Reform is underway but there are differences between companies so it’s something we think about a lot and do a lot of due diligence on,” she adds. “The ease of doing business across frontier markets has improved but we have to pick through which areas are better and worse.”

Fletcher, meanwhile, calls Egypt “the IMF poster child for structural reform” as its government has made huge progress is reducing its deficit, while enjoying the spoils of a tourism boom and thriving energy exports.

Companies, as well as countries, in the region should be taken on a case by case basis. For example, in the banking sector, which is a major beneficiary of increasing wealth in the region. Innes says: “[Whether a bank is investable] depends on the economic cycle, credit and competition. We tend to look for fairly plain vanilla banks – those which focus just on domestic deposits and lending, we don’t international, financial conglomerates.”

Myth 4: More risk always means more reward

The reason investors typically expose themselves to riskier assets is because of the potentially greater rewards on offer. Frontier markets are at an earlier stage of their development than developed countries or even emerging markets, which should mean they can grow at a faster rate.

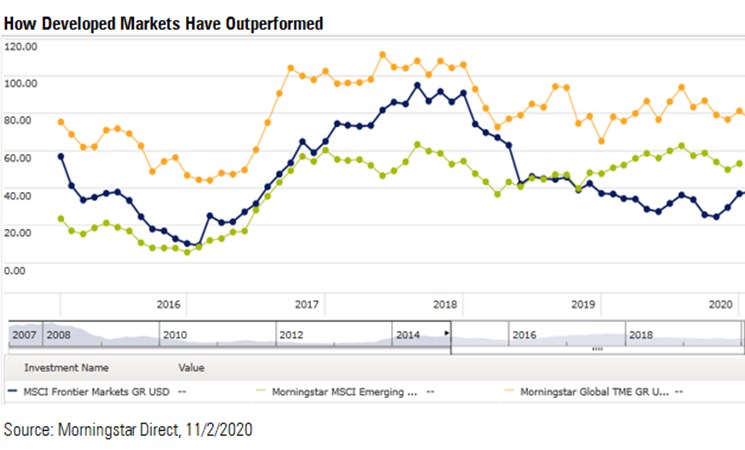

But the results can be mixed. Mark Preskett, portfolio manager at Morningstar Investment Management, says: “Investing in frontier markets has, at times, provided investors with exceptional returns. For example, the index climbed 32% in 2017, well ahead of global and emerging markets. However, over the long-term, the asset class is well behind both.”

In the final quarter of 2019, the MSCI Frontiers Markets Index lagged the MSCI Emerging Markets Index – the two were up 6.64% and 11.84% respectively over that period. Over the year as a whole the two indices produced similar returns, at 18.42% for Emerging Markets and 18.34% for Frontiers.

The chart below shows that over the past 5 years, investors would actually have done best by investing in a developed markets index (orange) rather than frontiers (blue) or emerging markets (green).

Preskett has other concerns too. He says: “There are three main issues to consider when accessing these markets: concentration, liquidity and cost.”

Around half the MSCI Frontier Markets Index is invested in just two countries – Kuwait (38%) and Vietnam (16%) - and sector and stock concentrations are also high. He adds: “Not all funds operating in this space offer daily dealing, which could be a concern for investors wanting to buy or sell.”

Fees are also a sticking point, he adds, with the ongoing charges of funds in this area often higher than those focusing on other markets. And while fees are not the be all and end all, Preskett points out: “They will take a decent chunk out of an investors’ returns over the long-term compared to a cheaper index investment.”

This article initially appeared on Morningstar.co.uk