One of the most disheartening aspects of investing is when the fund displays a seductive return, but your very own investment in it shows a rather dismal one. There is a term for this - the Behaviour Gap.

Behaviour Gap is the difference between the rate of return an investment produces in a certain period of time, and the rate of return that an investor actually earns in that very investment.

We set to find out if this is prevalent or not. The report titled Mind The Gap studies this pesky gap between the investment return and investor return. And our findings indicate that such behaviour is prevalent, but varies across fund categories.

You can read the methodology here.

Click on the below images to enlarge. Data is as on June 30, 2022.

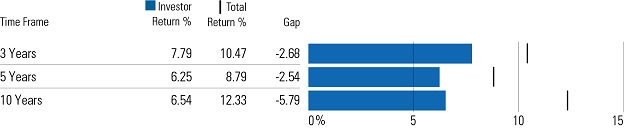

Overall, asset-weighted returns across all the mutual fund categories, which are the returns experienced by

investors, lagged the reported total returns for all asset classes over the 3-year, 5-year, and 10-year

period. A gap of negative 2.68% per year for three years has eaten away almost a fourth of the returns earned

by funds.

Similarly, while this gap was reduced marginally over a 5-year period to negative 2.54% per year, the gap

was significant enough to eat away more than a fifth of the returns the funds earned. Over a 10-year period,

the investor gap widened to a massive negative 5.79% per year.

Investor returns are more telling as they include the impact of cash inflows and outflows. This is represented

in the investor gap. The data above clearly shows that investors generally have been poor at timing the entry

and exit from funds over a longer period.

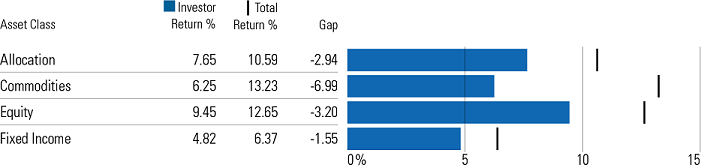

Look at the two charts below.

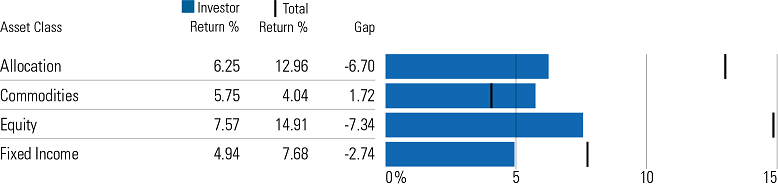

Precious metals/commodities are known to be historically extremely volatile. Over a 3-year period, the investor gap in commodities was almost negative 7% per year, which ate way more than half the returns the fund generated over that period. Over a 10-year period, the investor gap in commodities was positive, meaning the buy-and-hold approach failed in this asset class and investors were rewarded for their timing. That said, it is extremely difficult to get right.

3 YEARS

10 YEARS

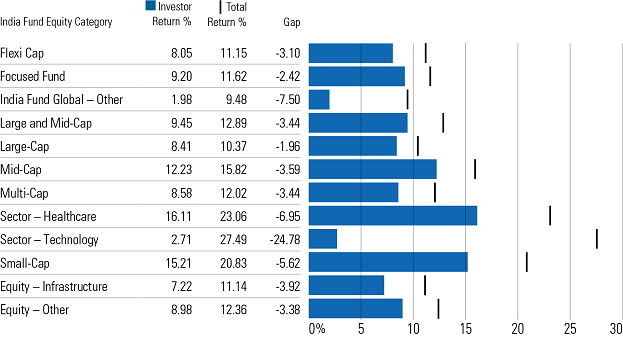

Let's take a look only at equities over a 3-year period.

Categories like global funds, healthcare, and technology were among the outliers.

Since the pandemic in March 2020, categories like healthcare, technology, and global funds performed remarkably well when the markets rebounded. This, in turn, led to these categories receiving large amounts of flows as investors took notice.

Sector funds are particularly prone to performance-chasing, with investors often piling into popular sectors after a strong showing and then bailing out when they fall out of favour. Just look at the Investor Gap for the technology sector; the highest at -24.78% per year over a 3-year period!

It is important to highlight that early in 2022, SEBI had restricted overseas investments by mutual funds, leading

to many global funds not having inflows during that period, which, in turn, has also led to the gap being large.

What is the reason for this gap between the fund return and investor return?

The gap could be causes by various reasons, or a confluence of them: Timing the market, buying (or selling) on the basis of recent performance, chasing after a fad, or just deciding to leave the market when it's temporarily down. All these decisions can be destructive to your portfolio.

What leads to the behaviour gap is not that the fund is a dud. It is behaviour driven by emotion or latest performance.

You’re more likely to see the value of your investments rise over an extended period if you leave them alone. Stop chasing latest performers. Stop continually switching your holdings to try and beat the market. Stop timing the market. Automate as much as possible.

What must you, as an investor, take away from this study?

Focus on holding a small number of widely diversified funds and avoid narrowly defined funds; the latter tend to have the widest return gaps.

The "specialized funds" seem tempting. But they really may not be your cup of tea. Theme-based funds, sector funds,

and smart beta funds to cite a few. Most investors are better served by keeping things simple and sticking with plain-vanilla, broadly diversified funds. More broadly defined core offerings such as large-cap and flexi-cap have done significantly better than narrower offerings, such as sector funds and thematic funds.

Similarly for fixed-income categories, while overall investor return gaps are narrower than equities, core categories such as short duration, have narrower gaps as compared with more-volatile categories such as dynamic bond or gilt funds.

- Don’t make investments purely based on past performance.

Often investors are swayed into investing into the top-performing funds over the short term. This often results in a big gap in investor returns. Funds go through cyclical periods of underperformance due to style headwinds. Investors often end up selling out of recently underperforming funds and buying into recent outperformers, only for the trend to reverse, resulting in large investor return gaps.

Take technology funds as an example as to why narrow funds should be approached with caution, and why past performance can mislead. They gained immense interest since the pandemic, but most flows came into these funds after the sharp run up, thus leaving investors with significant return gaps.

- Be hands off to some extent.

Automate. When you do so, the the opportunities to act out of emotion diminish. Opt for systematic investment plans (SIPs). Rupee-cost averaging often gets a bad rap because it creates a drag on returns when market returns are generally positive. Investors who have a lump sum available will usually earn better results by putting it all to work as soon as possible instead of investing it gradually over time (which means keeping some assets on the sidelines). Investors who have the means—and the temperament—to buy and hold over the long term will likely enjoy the best results.

The buy-and-hold approach depends on two key things, though:

1) having money available to invest all at once, and

2) having enough discipline to buy and hold despite the vagaries of the market.

Unless they're fortunate enough to have large sums of money available via inherited wealth or other windfalls, though, most investors can only invest a little at a time as money becomes available—for example, setting aside a certain percentage of each paycheck to invest for retirement.